In earlier AfroECO articles, we explored WHO’s guidelines on sanitation and health and South Africa’s progress in eradicating unsafe pit toilets. This third article continues that conversation by focusing on a critical question:

How do unhygienic pit toilets specifically affect the health, dignity, and safety of women and girls?

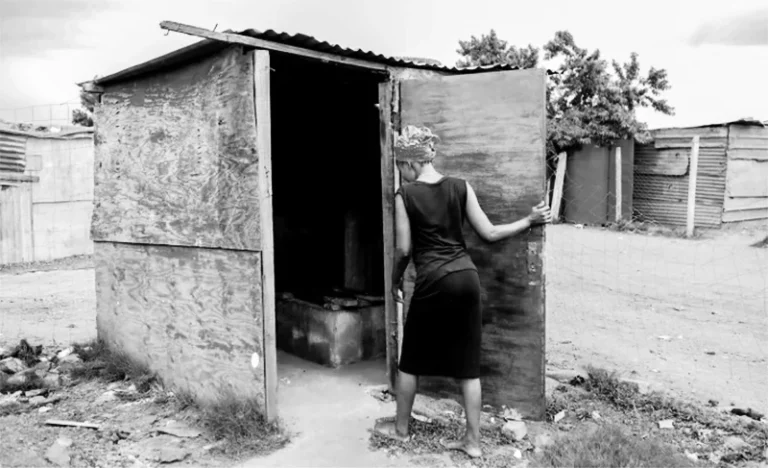

Across rural communities, informal settlements, and under-resourced schools, thousands of females still rely on pit latrines that are dirty, unsafe, or poorly maintained. These conditions don’t just cause inconvenience—they contribute to infections, missed school days, chronic anxiety, and a loss of dignity.

Why Females Are Disproportionately Affected

Pit toilets are often seen as a low-cost “step up” from open defecation. But when they are unhygienic—poorly cleaned, structurally unsound, badly ventilated, or left overflowing—they become high-risk spaces, especially for women and girls.

- More frequent usage needs: Females generally use toilets more often due to menstruation, pregnancy, and caregiving responsibilities, increasing their exposure to pathogens in dirty facilities.

- Lack of privacy and dignity: Doors that don’t close, missing locks, no lighting, and foul smells make it difficult to manage basic needs—especially during menstruation.

- Nighttime safety risks: Fear of harassment or assault at night leads many women to “hold it in,” which can contribute to urinary tract infections (UTIs), constipation, and bladder problems.

Health Risks: From Infections to Long-Term Consequences

Unhygienic pit latrines expose users to multiple health threats. For females, these threats are layered on top of biological and social realities that make them more vulnerable.

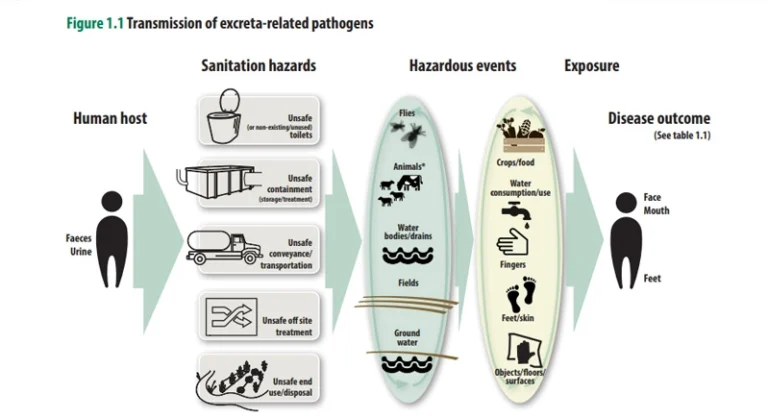

1. Exposure to illness-causing pathogens

Dirty slabs, contaminated seats, overflowing pits, and standing wastewater can harbor bacteria such as E. coli, Salmonella, and other enteric pathogens. Women who care for children or sick relatives are often in and out of these spaces, increasing their contact with contaminated surfaces.

2. Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) challenges

Many pit latrines are not designed with menstrual hygiene in mind. They lack water, handwashing stations, disposal bins and basic privacy. This can force women and girls to use unsafe materials or delay changing menstrual products, increasing the risk of reproductive tract infections (RTIs) and severe discomfort.

3. Psychosocial stress and anxiety

When every toilet visit feels unsafe, embarrassing, or degrading, it places a heavy mental burden on users. Girls may avoid using the toilet at school or stay home altogether when they are menstruating, leading to lost learning time and lower confidence.

4. Increased caregiving burden

Poor sanitation affects entire households, but women usually carry the responsibility of caring for sick family members. Diarrheal diseases, worm infections, and other sanitation-related illnesses translate into more unpaid labor, missed work opportunities, and deepening gender inequality.

The Hidden Risk of Unsafe Pit Emptying

In many communities, pit latrines are emptied manually, often without protective clothing, proper tools, or safe disposal options. This practice exposes sanitation workers and nearby households to high levels of pathogens, which can contaminate soil, groundwater, and household environments.

Women who fetch water, wash clothes, or cook with contaminated water are then indirectly re-exposed to those pathogens, reinforcing a cycle of infection that is rooted in inadequate sanitation systems.

What WHO Says About Gender-Responsive Sanitation

The World Health Organization (WHO), through the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) with UNICEF, makes it clear that sanitation systems must be designed and managed with gender in mind.

Our earlier article on WHO’s sanitation and health guidelines highlights how improved sanitation, including well-designed ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrines, can reduce disease risks—but only if they are kept hygienic and safe for regular use.

WHO guidance calls for risk-based sanitation planning, better protection for sanitation workers, and stronger integration with public health programs. Crucially, it stresses that women and girls must be included in decisions about how toilets are designed, located, and maintained.

South Africa’s Progress—And the Gaps That Remain

South Africa has taken important steps to address the pit latrine crisis, especially in schools.

As we discussed in our article on eradicating pit toilets, the Sanitation Appropriate for Education (SAFE) Initiative and related programs aim to replace unsafe school toilets with safer, more dignified solutions.

However, many challenges remain:

- Households in rural and informal areas still rely on unimproved pit latrines.

- Maintenance and cleaning are often underfunded or poorly managed.

- Girls continue to miss school due to inadequate menstrual hygiene facilities.

- Sanitation workers and communities are still exposed to unsafe emptying practices.

Addressing these issues requires a combination of government action, community involvement, and innovation from the private sector and social enterprises.

What Needs to Happen Next

- Designing toilets with menstrual hygiene in mind—including water, bins, privacy, and safe disposal.

- Upgrading or replacing dangerous pits with safer, hygienic systems such as properly managed VIP latrines or waterless eco-toilets.

- Training and equipping sanitation workers to empty pits safely and dispose of waste responsibly.

- Involving women and girls in decisions about toilet location, design, and maintenance.

- Strengthening public–private partnerships to scale up affordable, sustainable sanitation technologies.

Towards Safe, Dignified Sanitation for Every Woman and Girl

Unhygienic pit latrines are not just an infrastructure problem—they are a women’s health issue, an education issue, and a human rights issue. By combining strong policy, community engagement, and practical, gender-responsive design, South Africa can ensure that no woman or girl has to risk her health or dignity simply to use the toilet.

At AfroECO, we believe that safe sanitation, effective hygiene products, and cleaner environments go hand in hand.

As the country continues to move away from unsafe pit toilets, we remain committed to supporting households, schools, and communities on the journey to healthier, more dignified sanitation for all.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *